library(data.table)

library(flextable)

library(ggplot2)

library(irt)

library(mirt)Loading required package: stats4Loading required package: latticeAlex Wainwright

November 27, 2025

This post discusses a measurement paper that leaves a lot to be desired. The aim isn’t to criticise the authors personally, but to show the substantial problems in the analyses and highlight steps readers should avoid in their own work.

Loading required package: stats4Loading required package: latticeThe paper attempts to equate two test forms (A and B) designed to measure academic ability in Natural Sciences. Equating places scores from one form onto the scale of another using a small set of common “anchor items” (in this case, eight items). The remaining items are unique to each form.

A total of 281 students participated (Form A: 141; Form B: 140). Responses were modelled using the Generalized Partial Credit Model (GPCM) due to items being scored 0–3. The authors had no prior evidence that either test form was valid, reliable, or well-functioning.

The reported fit of the GPCM models were as follows:

Form A: TLI = .511, CFI = .549, RMSEA = .0286, SRMR = .081

Form B: TLI = .542, CFI = .578, RMSEA = .0526, SRMR = .088

The authors conclude the RMSEA indicates “good fit” and move on with the analysis.

This is incorrect.

TLI and CFI are far below any acceptable threshold (common cut-off is ≥ .95 for IRT models; even the most lenient standards would reject values this low).

No χ² (or equivalent) test is provided, which is standard practice.

RMSEA can appear artificially “good” in poorly identified models, especially when parameters are unstable or the model is oversized relative to sample size.

Taken together, the model clearly does not fit the data, and the results should not be interpreted without further investigation.

Below is an excerpt of Form A item parameters (10 of the 30 items).

If we use .70 as a minimum discrimination (a) value, all items fall below that threshold. One item even has a negative discrimination, meaning higher-ability students are less likely to score well, which is a red flag for misfit or miscoding.

Thresholds (b1–b3) are also severely disordered, extremely large, and inconsistent with realistic category structure. Given the poor global fit and small sample, these estimates should be treated as unreliable.

# Form A Item Bank

form_a_parameters <-

fread("form_a_parameters.txt")

form_a_parameters |>

as_flextable() |>

colformat_double(digits = 3)Items | a | b1 | b2 | b3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

character | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric |

A1 | 0.445 | 3.157 | 0.735 | -1.001 |

A2 | 0.484 | 1.992 | -1.356 | -0.206 |

A3 | 0.404 | -2.737 | -0.843 | -5.518 |

A4 | 0.222 | 0.158 | 6.407 | 2.670 |

A5 | 0.222 | 8.335 | -5.422 | 4.561 |

A6 | 0.112 | 15.022 | -8.322 | -4.688 |

A7 | 0.318 | 0.463 | -0.561 | -1.069 |

A8 | 0.118 | 11.285 | 0.456 | 17.818 |

A9 | -0.021 | -8.952 | -75.053 | -25.707 |

A10 | 0.197 | 3.462 | 0.803 | -1.320 |

n: 30 | ||||

The same issues appear in Form B, shown below.

# Form B Item Bank

form_b_parameters <-

fread("form_b_parameters.txt", fill = T)

form_b_parameters |>

as_flextable() |>

colformat_double(digits = 3)Items | A | b1 | b2 | b3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

character | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric |

B23 | 0.192 | -4.601 | -0.125 | -5.614 |

B24 | 0.376 | 3.462 | -0.118 | -0.240 |

B25 | 0.387 | 4.746 | -3.474 | 2.716 |

B26 | -0.154 | -13.168 | -0.184 | |

B27 | 0.190 | 7.774 | -10.433 | 11.886 |

B28 | 0.381 | -3.562 | 6.557 | -7.262 |

B29 | -0.186 | -11.521 | 4.917 | -18.528 |

B30 | 0.054 | 14.996 | 10.455 | 16.409 |

B31 | 0.149 | 13.962 | -18.489 | 12.708 |

B32 | 0.407 | 4.116 | -4.161 | 4.773 |

n: 30 | ||||

A simulation is needed for one reason: the reported model is not trustworthy.

The model does not fit the data.

The item parameters are implausible and highly unstable.

Under these conditions, equating is irrelevant, if the underlying model is noise, then equating simply aligns one set of noise to another.

To demonstrate the instability, I simulate datasets using the reported Form A GPCM parameters 1000 times and re-estimate the models. This allows us to examine:

the spread of recovered item thresholds and discrimination estimates

the uncertainty in model-fit indices

In other words, I show what the authors did not: the amount of uncertainty in the reported results.

set.seed(2511)

form_a_bank <-

itempool(form_a_parameters, model = "GPCM")

simulation_results <- lapply(1:1e3, function (i) {

resp <- sim_resp(form_a_bank, rnorm(141))

gpcm_model <- mirt(resp, itemtype = "gpcm", verbose = F)

list(

model_fit = M2(gpcm_model),

item_parameters = coef(gpcm_model, IRTpars = T, simplify = T)$items

)

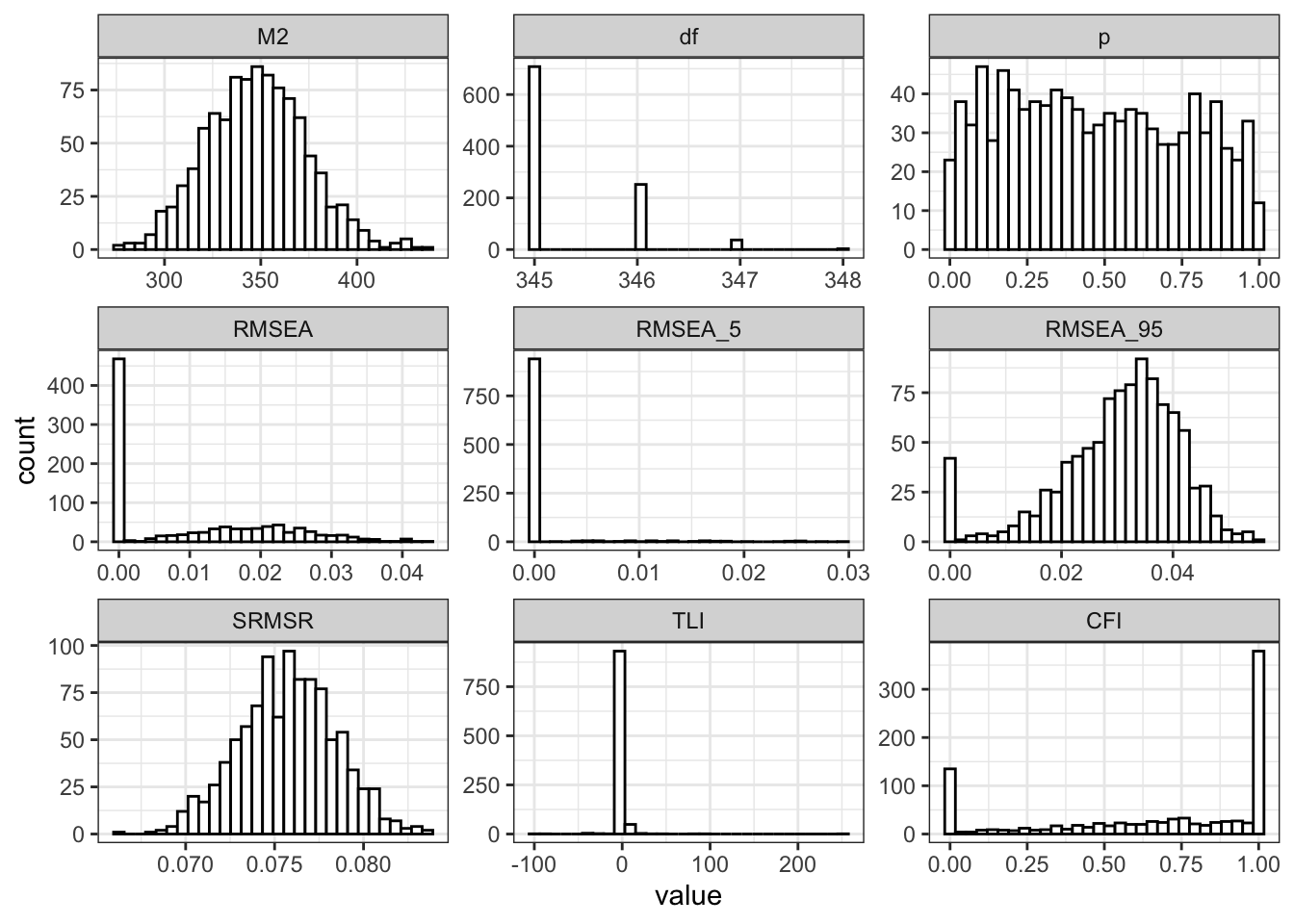

})Across the 1000 replications, we replicate the findings of the author: “good” RMSEA/SRMSR paired with poor CFI/TLI (Table 3). However, the standard deviations of CFI and TLI are large, showing that the fit statistics themselves are unstable. The point estimates of the original paper are not showing the full picture: the estimates are extremely variable.

model_fit <-

lapply(simulation_results, function (x) x$model_fit) |>

rbindlist(fill = T)

model_fit[, .(

"Fit Measure" = names(.SD),

"Mean" = apply(.SD, 2, function(x) mean(x, na.rm = T)),

"SD" = apply(.SD, 2, function(x) sd(x, na.rm = T))),

.SDcols = c("RMSEA", "SRMSR", "TLI", "CFI")] |>

as_flextable() |>

colformat_double(digits = 3)Fit Measure | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

character | numeric | numeric |

RMSEA | 0.011 | 0.012 |

SRMSR | 0.076 | 0.003 |

TLI | 1.007 | 10.580 |

CFI | 0.678 | 0.363 |

n: 4 | ||

To visualise this, Figure 1 plots the distribution of each fit measure across replications. The spread is wide, especially for the incremental fit indices.

model_fit[, simulation_run := .I] |>

melt(id.vars = "simulation_run", variable.name = "fit_measure") |>

ggplot(aes(x = value)) +

geom_histogram(

colour = "black",

fill = "white"

) +

facet_wrap(~fit_measure, scales = "free") +

theme_bw()

Next, we examine the recovered item parameters. For each simulation, I extracted the re-estimated discrimination and thresholds. Table 4 summarises the mean and standard deviation per item and per parameter. The results show what the paper never reports: massive instability in several thresholds, particularly for items with already questionable estimates.

model_parameters <-

lapply(simulation_results, function (x) as.data.table(x$item_parameters, keep.rownames = T)) |>

rbindlist(fill = T)

model_parameters[,

.(

"Fit Meaure" = names(.SD),

"Mean" = apply(.SD, 2, function (x) mean(x, na.rm = T)),

"SD" = apply(.SD, 2, function (x) sd(x, na.rm = T))

),

by = c("Item ID" = "rn"),

.SDcols = c("a", "b1", "b2", "b3")] |>

as_flextable(max_row = 20) |>

colformat_double(digits = 3)Item ID | Fit Meaure | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

character | character | numeric | numeric |

Item_1 | a | 0.465 | 0.154 |

Item_1 | b1 | 3.478 | 1.564 |

Item_1 | b2 | 0.756 | 1.038 |

Item_1 | b3 | -1.151 | 1.123 |

Item_2 | a | 0.505 | 0.158 |

Item_2 | b1 | 2.137 | 1.124 |

Item_2 | b2 | -1.438 | 0.878 |

Item_2 | b3 | -0.271 | 0.643 |

Item_3 | a | 0.428 | 0.199 |

Item_3 | b1 | -3.382 | 4.758 |

Item_3 | b2 | -1.182 | 4.546 |

Item_3 | b3 | -7.381 | 13.477 |

Item_4 | a | 0.226 | 0.131 |

Item_4 | b1 | 0.563 | 11.962 |

Item_4 | b2 | 18.475 | 259.597 |

Item_4 | b3 | 9.416 | 148.147 |

Item_5 | a | 0.234 | 0.118 |

Item_5 | b1 | -1.276 | 282.750 |

Item_5 | b2 | 1.751 | 203.804 |

Item_5 | b3 | -3.691 | 235.424 |

n: 120 | |||

The pattern is clear:

Discriminations show modest variability.

Thresholds for several items explode, sometimes with SDs in the hundreds.

This confirms that the original parameter estimates are not stable enough to support equating.

The results reported in the paper cannot be trusted. The model does not fit, the item parameters are unstable, and the equating is performed on foundations that do not hold.

Before any equating could be justified, the authors should have validated the scale, checked dimensionality, examined category functioning, and ensured item quality. None of this was done. Instead, the analysis proceeds on the basis of a single favourable RMSEA value, while the remaining fit indices clearly reject the model.

The sample size is insufficient for the complexity of the model, many items behave pathologically, and there is no evidence that the test measures a single latent trait.

The simulation demonstrates what the paper did not: the estimates are highly unstable, the fit indices vary widely, and the recovered parameters exhibit enormous uncertainty. The published results give a false impression of precision.

As it stands, the findings are not interpretable and the paper’s conclusions are unsupported.